|

What a strange time we're all walking through right now. Children, parents, families are all being asked to do the impossible, and yet here we are, finding ways to cope, creating new routine, and finding inner resilience and strength we may never have known we had. You may be struggling with just how to communicate with your child(ren) not only about the state of the world, but also about their thoughts and feelings about it. You may also be wondering what you can do to support your child right now, especially when you as a parent may already have such a full plate, trying to juggle your own work, self care, your child's school work, family routine, chores, etc. Below, you will find many helpful tips and resources.

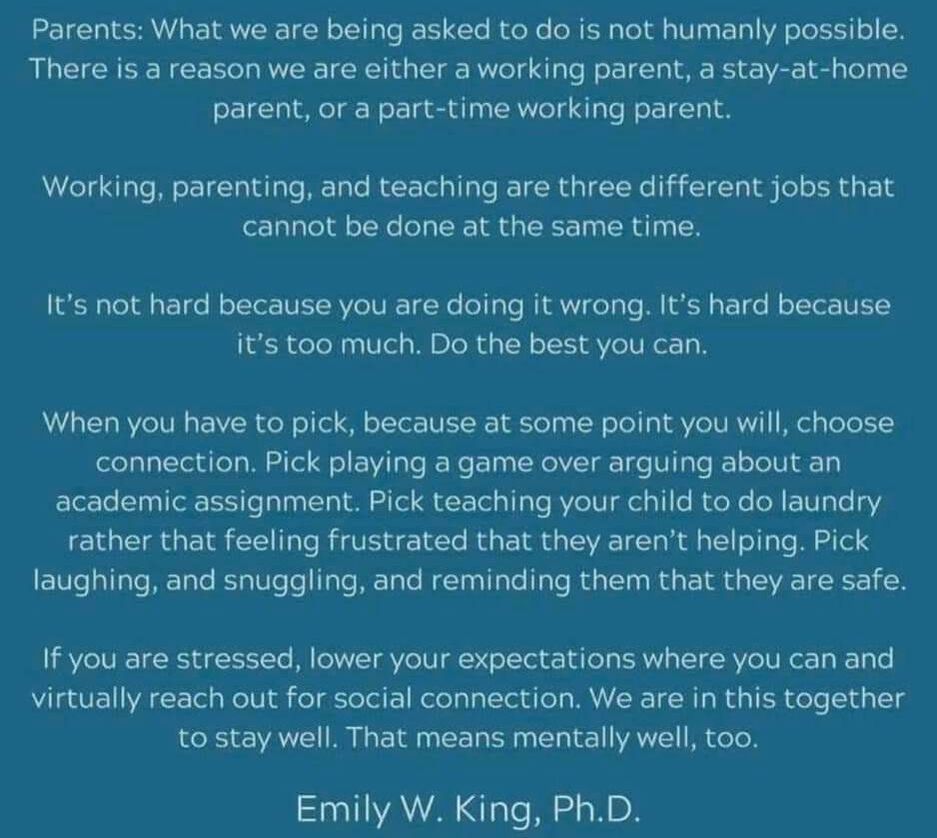

Talking to Children about COVID-19: There are 3 articles on our helping articles page that offer: 1. a really good list of both general considerations for all kids as well as some age-specific guidelines. 2. a comic for upper elementary and older kids (not appropriate for younger kids). 3. a great resource for lower elementary and younger with links to videos from PBS. Ideas for starting conversations with your child(ren): 1. Ask them what they know (listen without interrupting, validate feelings, and then find moments to correct any misperceptions or misinformation. 2. Ask them about what they like and don't like about being home all the time. 3. Ask them what they miss about how things were before. 4. Ask them about the pros/cons about school at home versus school at school. 5. Ask them to tell you about what they're grateful for. It can be fun to take turns coming up with ideas to these questions together, as a family. Helping Your Children Cope: Here's a list of ideas that may support your child/family in coping with COVID-19 related changes. 1. Spend time in nature 2. Find ways to stay connected with friends and family 3. Spend positive time alone 4, Take advantage of free online offerings of yoga, mediation, mindfulness through apps and videos 5. Find ways to connect to your family's spirituality 6. Get creative with rituals, celebrations, rites of passage 7. Reconnect to old hobbies (or discover new ones). Share a hobby with your child. Teach them something new. 8. Get creative with accessing positive activities. Find out what extracurriculars are currently being offered online. 9. Exercise, get active. 10. Find ways to be of service. Teach your children the value of helping others, donate to a local food drive, help a local family in need, show kindness to someone in the house. 11. Practice positive perspectives and reframing. Your child may need support to shift from a worry focus to all of the things your family is doing to stay safe and healthy. Supporting Parents: Please be gentle with yourselves. Take time for self care. Remain calm and neutral whenever possible. Model positive coping strategies for your children; they are paying attention. We will get through this together.

0 Comments

The teen years can prove to be challenging for families, as it is a time of great transition, with teens seeking more autonomy, wanting to think and make decisions for themselves, and parents often struggling with when & how to let go while still retaining the hierarchy of parental authority. When children are younger, phrases such as "because I said so" or "because I'm your mother" may sometimes be effective. As children become teenagers, it's important to consider a shift to negotiating rules, for example, listening to the teen's point of view, thinking it over and then returning with the final say as a parent. What's also helpful is providing reasons behind rules, such as relating curfews to the concept that you worry when they're out to late and you'd like to get a good night's sleep. Also, be weary of getting into arguments over teenagers reactions to rules, such as eye-rolling, grumbling or them responding with "I don't care." Instead of taking these reactions as a personal affront or disrespectful, as many parents' initial thoughts might lead them to believe, try shifting your perspective to the idea that these responses are simply one way teens express their feelings. Instead of overreacting, try tolerating grumbling, while expecting obedience. It's more important whether or not teens are following the rules than how they react when the rules are being stating or re-stated. It's also important for parents to be as flexible as possible, recognizing that enforcing rules around what teenagers do at home is where your control lies, while enforcing rules about what teens do outside the home isn't realistic, because you aren't present. As another perspective shift, think about the idea that we all have internalized tapes that play in our minds, whose voices are often those of our parents. These voices become part of teenagers' developing consciences. When parents are there trying to control things, teenagers may rebel. Instead, trust that all that you've taught them, said, and modeled is inside of them and that those tapes will be playing as they consider what is right/wrong when it comes time to make decisions. Additionally, It's important to be available for teens as a support and a listening ear, as having a trusted adult to talk to can relieve stress and strengthen resilience. Take an interest by asking specific questions without going into lecturing, threatening, or punishments as a response. Teenagers often keep things from their parents that they believe their parents may give them a hard time about. Work to minimize additional stress you, as parents, put on teenagers, because a stressful environment can lead to stress-relieving activities in attempts to self-soothe that may not be healthy/productive. As a final thought, although teenagers may not say this aloud, the approval of their parents still matters to them. It's okay to say things such as "I don't like when you come home later than your curfew." Parents can reduce arguments when teens break a rule by utilizing the following:

a. Make a clear statement acknowledging that a rule was broken b. State that this type of behavior is not acceptable c. Declare the rule still stands. For example: "You came home past your curfew yesterday. This is not acceptable. I want you home by 10pm and on time moving forward." Although they may respond about how it isn't fair or that all of their friends have later curfews, and that you can't make them follow the rule, you can respond with: "That's correct, I can't make you, but that is when I want you home by." Again, although they may respond with an eye roll, grumble or statement of "I don't care," they do care and the rule will have some impact on their decision making in the future. And since teenagers still care about parental approval, continue to give them specific positive praise, acknowledging when they do do something you like. Reference: Nichols, M. P. 2009. Inside Family Therapy: A case study in family healing. Allyn and Bacon. Boston, MA. From birth, children are our mirrors. They learn to imitate our facial expressions, sticking their tongues back out at us for a laugh or a smile, showing us they can do that trick too. They watch us intently as they grow, for better or worse, picking up on our language, mannerisms, behaviors and emotions. Children are like perceptive little sponges, soaking up the world around them. As they grow and begin to test limits more and more, they often display behaviors that we may not be fond of. They may yell, fight with siblings, talk back, refuse to do something, hit, tantrum, and other behaviors that can make parenting a challenge. Whenever a parent talks with me about the things they wish their child was doing, such as use feeling words to express themselves, calm themselves down when they're angry, or cope with worries, I often ask parents if they modeling any of those healthy behaviors that they would like to see in their children? Do you remain calm, counting deep breaths when you're angry, or do you sometimes yell and lose your temper? Do you punch a pillow or using art to express your frustrations or do you go straight to punishments and consequences? Do you use feeling words to describe how you feel aloud in front of your children so they can learn about all the different types of emotional states? Nine times out of ten parents are wanting and wishing that their children would behave better, without practicing those positive behaviors themselves. Remember, children watch and learn from those around them, so if we want their behaviors to change, we need to ask ourselves what their behavior may be trying to show us? How are they being our mirrors today? When we can see children's behaviors as mirrors and ask ourselves these questions, we can begin to increase our awareness of how interconnected we are and take a look at how we can model positive coping skills for our children. So adults, next time you're angry or frustrated, see if you can say aloud how you're feeling, showing your children how you can cope with anger and that it is possible to feel angry but express that anger in a healthy way. Using words, art, breath, counting, pillow punching, feet stomping, and writing are all great ideas for anger expression. We can be the change we wish to see in them, trusting that children will continue to be our reflection in the mirror and learn from what they see.

Children's anger and aggression can sometimes be challenging for parents and adults to manage. Parents may try different types of responses, some of which may sometimes seem to work, and others that just don't work, but parents aren't always sure what else to try. Typically, parents report that they respond to children's anger/aggression with the following: -raising their voice/yelling -spanking -time outs -asking the child why they did something -taking something away from the child (punishment). These responses don't usually yield the results that parents are hoping for. The first two, yelling or spanking, can escalate the situation. They also model the exact opposite of the positive behavior that a parent is trying to teach the child. Time outs work great with some children when they're used appropriately, but with other children they escalate the situation, making the child more upset. Asking a small child why they bit their friend at pre-school is often not helpful because the child may not know why, or how to verbalize why, and if the child were old enough to respond, often these types of discussions don't result in positively, and instead may create more anxiety. And finally, taking something away from a child doesn't offer the child any incentive for correcting their behavior. If they've just lost their phone and can't earn it back, why should they change/correct their behavior? Here are some alternatives to try. Start modeling appropriate verbal expressions of anger. Use words like angry, mad, frustrated and annoyed in sentences when situations arise. For example, as the adult, let the child hear you say, "I'm so frustrated that dad got the remote before I did." or "I'm annoyed these dishes didn't come out of the dishwasher clean" or "I'm so mad that the dog peed in the house again!" So often adults want children to use words to express feelings when the adults around them aren't modeling any feeling words. Try making it fun by planning out role play scenarios that 2 parents/adults can act out that the children can witness or overhear. Another important thing to keep in mind about anger is to offer children appropriate alternatives to release it. Here's where you can use the 3 step limit setting (see June 2015 blog post), including naming the feeling, stating the limit and offering an alternative behavior . Some ideas for step 3 are:

Teaching and modeling deep breathing, yoga and meditation can go a long way to help children find ways to listen to their bodies, self-sooth and find peace in stressful situations. Siblings...they can be best of friends one minute, providing companionship and entertainment for each other, and enemies the next, fighting and hurting each other's feelings. What is a parent to do? How can caregivers navigate sibling ups and downs?

I've found the #1 most helpful tool an adult can use when interacting with child siblings is narration. So often parents fall into the comfortable traps of communicating to their children by either teaching/educating, giving commands, or asking questions. Parents also have a tendency to find themselves in the roll of referee, which doesn’t allow children to enhance their own skills of conflict resolution, and can even escalate, instead of de-escalate sibling conflict. Instead, when caregivers are narrating children's experiences, children find themselves able to problem solve on their own, increase their own communication skills, empathize with their siblings, and resolve issues without adult direction. Here's how it works: Let's say a pair of siblings is playing together in the living room. Maybe one is playing with the helicopter while the other is playing with the dollhouse. All of a sudden the child playing with the dollhouse decides the helicopter looks really fun and they need it for their pretend play story. If an adult is in the room and watching they would most likely be heard saying things like: you have to share...or...he was playing with that first...or...you have to give that back, no grabbing...or...you need to wait your turn. Instead, what if the playtime looked and sounded more like this: Marie says: "I want the helicopter" Johnny replies: "No, I'm playing with it." Marie looks upset. Observing adults narrates: "Johnny it looks like you're using the helicopter for your story... Marie...I see you really want a turn with the helicopter. Sounds like Johnny isn't done playing with it yet. Marie, it seems like you're really feeling disappointed that Johnny isn't ready to share yet." Usually at this point either Marie will find something else to play with for a while or Johnny will give her a turn. Either way, the children are able to understand where the other person is coming from because the adult is narrating the experience and feelings. The important things to remember about using narration are to try to talk about what's happening, what's going on, what the children are doing and how they are feeling in statement form, as if you are announcing a football game. There are no questions or directions, but simply being 100% present with your children without any distractions. It can be helpful to set a timer for 5 or 10 minutes when you're first practicing so both you and your children can know when "special play time" beings and ends. However, narrating can be used outside of pretend play and in a variety of situations. If you'd like to learn more about using child-centered narration in a variety of settings, you may want to check out chapter 1 of "How to Talk so Kids Will Listen, and Listen so Kids Will Talk." In the event that narration does not lead to children resolving the conflict on their own and you do need to intervene, it is still best to refrain from the role of referee. It doesn't matter who started it, who did what first. If you're going to intervene, have both children take a break in their rooms so they can calm down, get some breathing room, and both have the same consequences for the sibling conflict. Setting limits calmly can be one of those tricky things for adults, especially in certain situations or when we've already had a trying day. Here's a simple 3-step formula for setting limits that can be used in almost any situation.

1. Validate what your child is trying to communicate/how they feel. e.g. You really want to play with that train. It's so hard to wait sometimes. 2. State the limit. e.g. We can't grab toys from our friends. 3. Offer an alternative. e.g. Let's ask if we can have a turn. Encourage your child to ask for a turn, "Go ahead, ask Ben if you can have a turn." If Ben says no you can start the formula over again in a different way. 1. Validate the feeling. e.g. You're so sad Ben isn't ready to share yet. 2. State the limit. e.g. We can wait a little and ask Ben if she's ready to share then 3. Offer an alternative. e.g. Or we can play with something else. Which would you like to do? (Offering a limited choice can be a good idea to help a child feel in control when they're feeling powerless.) Words, phrases and tones to avoid: Stop that! Don't grab! You know the rules! Why'd you take his toy? You know better! That's it! I've had enough of your behavior today! You'd better start learning to share! What's wrong with you? These kinds of responses communicate to children that there is something wrong with them, that they are bad and lack the ability to self regulate. Instead, we want to communicate positive messages to our children, helping them to learn about their feelings and the world around them and how to navigate that world so that they can be successful in it and feel good about themselves. One of the challenges many parents face when communicating with their children is figuring out how to help their children feel heard and understood. When communicating with kids, parents can easily fall into patterns of giving commands, asking questions, teaching or trying to fix things for their kids. However, an alternative means of communicating can include validating statements, which can produce more positive parent-child interactions and relationships. Some benefits of using validating statements can include parents feeling more centered and calm, and children feeling more independent and self-regulated. With a little bit of practice, validating statements can become second nature. It's easiest to imagine of yourself as a narrator, making statements with an empathic tone to describe what's happening in a non-judgmental way that sums up what your child is trying to communicate.

Some examples of validating statements are:

|

Crystal ZelmanLCSW, CCLS, RPT-S Categories

All

|